Marlon Brando in, On the Waterfront, 1954 Credit: Columbia Pictures

The mile-square city of Hoboken sits on the New Jersey waterfront directly across the Hudson River from lower Manhattan. For strangers or visitors, its history conjures a number of cursory fast-facts, the most notable claims to fame being the birthplace of Frank Sinatra and baseball. Some may even know Hoboken was the filming location of the 1954 Oscar-winner, On the Waterfront, starring Marlon Brando. The film painted a portrait of the struggles for dockworkers on both sides of the river: the teamsters and longshoremen against a system entrenched in mob and political corruption.

Life On the Waterfront.

In many ways, the Brando movie underscored a life that was more real than fiction at the time. It was well known that organized crime had a stronghold on the shipping ports in the area, often extorting dockworkers and union officials for kickbacks in order to work each day. In fact, the Waterfront Commission was created by Congress in 1953 and still exists today as a watchdog intended to control the mob’s dealings in the shipping industry around New York City and Hoboken.

For most of the 20th century, much of Hoboken was home to the blue-collar, working class. For decades, they scraped by in the cold-water tenement flats, worshipped in churches and worked the docks and factories that authenticated the film’s backdrop. My own family was part of this Hoboken experience; the ‘old-timers’ worked and played within the one square mile. One grandmother worked at the Maxwell House Coffee Plant along the north end of the waterfront. Her husband and her father, both longshoremen on the docks. The other grandmother graduated from Our Lady of Grace Catholic School in 1938 and went on to secretary school in New York City. Her husband came from generations of longshoremen who worked the 38th Street piers in Manhattan.

Tom Hanley was a longshoreman in Hoboken for 38 years. At thirteen, he landed a bit role in On the Waterfront; a connection from a man whose rooftop pigeon coop Tom looked after. Tom’s father also worked the docks, and when Tom was four months old, his father disappeared. He’d been murdered in Greenwich Village by members of the Irish mob who were eventually sent to the electric chair for multiple murders in New York and New Jersey.

“We lived at 105 Hudson Street, a tenement, right across from where the police station is now. Now that street, at that time, had twenty-one bars on it. Each side of the tenement where we lived had a bar. And we knew everyone in the building. Some were longshoremen. Some had other jobs. They were all struggling, let’s put it that way.”

Tom Hanley

"They were the dregs of society, but there were alot of good men."

Excerpts from, “They Were the Dregs of Society, But …” – Recollections of Longshoreman Tom Hanley, created for the Vanishing Hoboken Oral History Project, by the Hoboken Historical Museum.

A Sad State.

Though they might have shared the common struggles, the people of Hoboken tended to self-segregate by neighborhood. Many were Irish, Italian or German, first or second-generation immigrants; perhaps they’d developed a clan-mentality to insulate their culture in the new world. Some owned brownstone row-homes, occupied by both immediate and extended family members. But the majority of families, large and small, struggled to afford the weekly rent in flats where, in 1950, nearly 15% of the units did not have a private toilet, and more than one quarter did not have running hot water. A decade later, a 1960 census noted nearly 48% of the housing in Hoboken was, “substandard by virtue of structural or plumbing deficiencies.”

In Need of a Plan.

And that was while the docks and factories were still in town. By the late 1960s, with more accessible ports in Newark and Elizabeth, the Hoboken piers were closed for business, and the factories moved further inland as well. Since the 1970s, the City of Hoboken has undergone a transformation of what the city’s planning boards have termed the “rehabilitation” of what had become derelict factories, buildings and piers. The plans were part of a Master Land Use Development Element, updated in 1979. They’ve been regularly updated to enable further gentrification in the recent decades. The most recent Master Plan was created in 2004. It underwent reexamination in 2010 and will be reexamined again in 2018.

Vanishing Hoboken.

At the time a revitalization plan seemed like the clear way forward; the city had been disinvested and was crumbling. The plan meant waterfront land, as well as apartment buildings inland, would be sold for development (or re-development), thus raising property values, taxes, and rents.

But in mega deals like these, many parties are usually involved, many with different interests, and not all of them above board. In the late 70s and 80s, key financiers attached to Hoboken’s rehabilitation stood to profit greatly from such investments. Most of the residents, however, did not. The properties of long-time homeowners or landlords of larger buildings were under speculation by large real-estate developers who were eager to force out the existing population and draw a higher-paying Manhattan crowd. Their plans for condominiums meant the old buildings needed to go, regardless of the tenants who lived in them.

It was around this time the city saw a rash of arsons among Hoboken’s larger tenements. Between 1979 and 1982, 51 people were killed and hundreds displaced. Anthony DePalma, a New York Times reporter at the time, covered the fires. His pieces recorded Hoboken residents’ suspicions that the buildings were being targeted for renovation or conversion. Many believed the arsons were an orchestrated way for owners to profit from the real estate boom by forcing out unwanted tenants, then selling the buildings to developers or converting them to condominiums immediately after collecting the insurance money.

Seeing is Believing.

My own father remembers it well. He expresses what seems to have been the common sentiment of locals at the time, “I remember the fires. It seemed like there was one every day for a while. They wanted the land and the easiest way to do it was to torch the buildings and collect [insurance]. You knew the mob was definitely behind it somehow, but you didn’t talk about it. When the docks closed, they diversified. Construction, unions, garbage removal, trucking and real-estate all work hand-in-hand. Everyone thought that, and no one did anything about it. Just like everyone knew the mob controlled the union and the docks back in my father’s time. Hoboken was a mess in every way.”

Whether the fires occurred deliberately or through bizarre coincidence is difficult to prove, since to date, no one has been identified for the crimes, if they were in fact crimes. In 1992, filmmaker Nora Jacobson released Delivered Vacant, a critically acclaimed documentary of the real-estate struggle, tenant harassment and gentrification in Hoboken, chronicled over an eight-year period during the 80s.

Trailer for Delivered Vacant, 1992. by Nora Jacobson

Striking Gold.

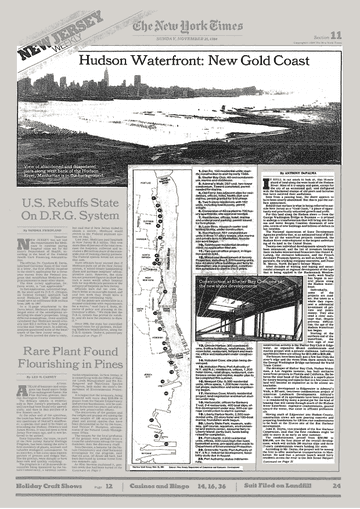

As early as 1984, DePalma reported, “the age of the Hudson waterfront has begun,” in what the National Association of State Development Agencies estimated as a $5 billion plan. Among the first to develop the new “Gold Coast,” were both local and international financiers. For example, Arthur Imperatore, a self-made trucking company tycoon from North Bergen bought a few miles for what seems like a song, $7.5 million. He called it Port Imperial, where he developed several condos along a riverside promenade. He also added a ferry port, and created the NY Waterway Ferry service which just reached 30 years in business, now with 17 terminals in New York and New Jersey. The ferry service generates over $80 million in revenue and carried 984,000 commuters in 2016. And the Fund for a Better Waterfront has been key in realizing the city’s vision for a walkable waterfront.

Today’s real estate prices must seem startling to former Hobokenites who were either priced out of the neighborhood or left for the suburbs before the tide turned. According to the New York Times, a four-story brownstone would set a would-be homeowner back around $25,000 to $32,000 in 1970, and by 1977 those priced had doubled. By the time the 2004 Master Plan was released, median townhome sales in Hoboken were $833,000 and by 2018, that number has doubled again to $1.6 million.

While these figures suggest the plan has been well-executed thus far, the numbers tell only part of the story. The city is thriving by most other accounts as well. Local shops, high-end luxury retailers and bistros line the small streets, service the 54,000 who now call Hoboken home. Ample green space and a now lively waterfront show the planning as children play and families enjoy a vision more than fifty years in the making. Today the media touts how, seemingly overnight, the city has become a hipster’s paradise.

And still the question tugs at those who have seen it develop first-hand, at what cost has this renaissance come about? Who will live to share how Hoboken was built, and rebuilt, on the backs of people like Tom Hanley and the others who stuck it out when bad turned to worse?

My father’s idea that the mob may have had a hand in bringing Trader Joe’s and the yoga-mom brunch-and-stroller set to Hoboken may seem ironic, or even comical. But it’s not as far-fetched as it one might think. The notion lends real continuity to the story of Hoboken’s tumult and growth of the last sixty years; a kind of gangster-supplied poetic justice that brings the city’s character full-circle as a result. It’s not especially comforting, either, to think Hoboken may still be engaged in untoward business on some level. But the thought might suggest that—after all the development, all the Master Plans, Town Halls, hipsters, frisbees and al fresco dining—just maybe, Hoboken hasn’t really strayed very far from its roots after all.

New York Times Archives articles about Hoboken from 1977 to 1987.